"Twin Peaks: The Return": The Structural Marvel of Chapter 8

By now, David Lynch is an elder statesman of film and television. The aw-shucks persona turned him into the crazy uncle everybody in your family thinks is weird, but you love to pieces. There is no calculation behind it, though. A disarming sincerity bleeds into his work, no matter the medium.

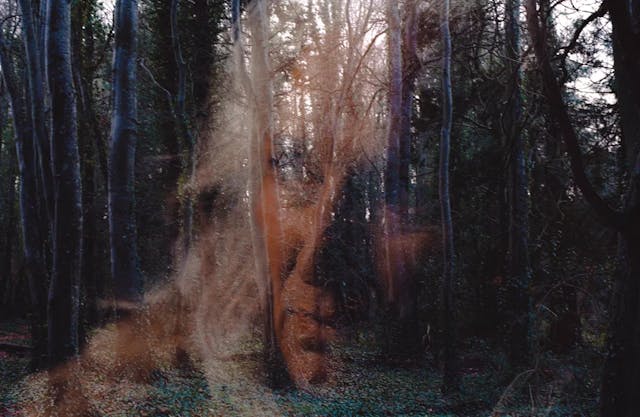

His uniqueness made him ascend to the pantheon of artists whose name has turned into an adjective. When people say something is Lynchian, they mean it as weird and creepy. That is a thankless simplification, taking middle-of-the-road Hollywood products as the standard by which we measure genius. It belies the beauty and warmth of his vision. His dreamlike Americana may be at constant risk of rotting away, but the idealism shines through. He always hints at the dark outside the light because he knows they depend on each other.

Lynch straddles many disciplines. His training as an artist predates his filmmaking and accounts for the painterly quality of his images. He is known to design furniture and is something of a performance artist. Check out his daily weather reports. O remember the time he planted himself in a busy street in Los Angeles with a live cow and a makeshift billboard, promoting Laura Dern for an Academy Award nomination for challenging tour de force of Inland Empire (2006).

He is one of the few filmmakers who have created influential work in both film and television. Many critics credit the original run of Twin Peaks (1990 - 1991), the episodic TV series he developed in tandem with Mark Frost, for planting the seeds of the new golden age of TV. Laura Palmer had to die so that Tony Soprano and Don Draper could live.

When Lynch created his take on prime-time soap operas, he was, in a way, moving backward. TV was a stepping stone to moviemaking, not the other way around. You did not choose the idiot box if you had the silver screen. But he did because he loved the medium and the possibilities of episodic narrative. He was not slumming by doing TV. He was thriving.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

The commercial possibilities of Twin Peaks gave the project a sort of multi-format life. The series pilot episode was edited with additional material to make it work as a stand-alone TV feature film for territories where the series would not find a broadcaster. Back then, in the pre-internet world, you would not have to worry about spoilers shared in real-time across the globe. Also known as the extended pilot, you can find it as an extra in a box set edited in the following years.

The rise and fall of Twin Peaks is the stuff of legend by now. The original plan was never to disclose who killed teenage queen Laura Palmer, but it crashed against the expectations of audiences and TV execs. He might have been able to keep the machine churning out for years on his terms, but it turned out to be just too popular to be left unchecked. People had expectations that needed to be addressed and fulfilled. So he did. He revealed the killer halfway through season 2, only for the ratings to plummet and ABC to cancel the series. You could not dangle a mystery in front of audiences and expect they would not want a resolution.

The experience did not sour Lynch away from TV altogether. He was back at it in the late nineties, pitching to ABC Mulholland Drive, another primer time soap, following the adventures of Betty (Naomi Watts), a wholesome ingenue trying to make it in Hollywood, while solving a dark mystery, like an adult Nancy Drew. The execs passed, but Lynch managed to find financing to expand the pilot, crafting a stand-alone feature film. It turned out to be one of his best works, regularly acclaimed as the best movie of the aughts.

Lynch floats from film to TV and back with ease. This ability speaks to his skills as a storyteller but also about the malleability of audiovisual drama. After the first two seasons of the series, Lynch surprised audiences with a movie: Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. People were expecting a continuation, but what they got was a flashback recounting the final hour of prom queen Laura Palmer. Side characters and brief references to events to come that Laura would not live to see - like Annie (Heather Graham), bloody and bruised, telling Laura about how the real Cooper was in the red lodge, while his evil doppelganger was out and about in our reality.

Twin Peaks The Return does not pick up in 1991, the day after evil Cooper smashes his head against a mirror. Time has passed. Just like in real life, some people have died. Others have moved away. Lynch opens up the focus beyond the northeastern town and its environs. Some scenes take us to New York, Las Vegas, and New Mexico. Old characters we hold dear appear. All of them are older, but some are not wiser. But we also get new ones: sons and daughters, new arrivals. And if you thought that two Coppers, one good and one evil, was too much, wait till you get a load of Dougie, a third version that would not be out of place in a Looney Toons cartoon.

While we try to make sense of our bearings, Lynch establishes a pretty straightforward structure. After spending most of the running time bouncing around different locations, showing the comings and goings of its characters, we dovetail towards the end into the Roadhouse. The Bang Bang Club is the local watering hole. It has been around since the beginning, but it looks larger and busier now. We get a brief scene between some of its patrons, usually seated in a booth. By the second or third episode, it becomes clear that these characters are not necessarily central to the plot. It is a digression, a dash of color, or an extra shot of weirdness. The conversation is usually abandoned or gives way to a musical number performed live at the venue, which we get to hear in its entirety into the closing credits.

It is an unusual way to close down a drama series episode. You would think you are watching a late-night variety show. And the repetition, one episode after another, lulls you into acceptance. Once you have internalized the rhythm, Episode 8 comes along and blows everything away.

The episode starts inauspiciously, with evil Cooper driving around at night with his minion, Ray (George Griffiths), looking for a secret location. The scene stretches to almost 10 minutes and then reaches an abrupt climax: Ray shoots Cooper, who falls to the ground, apparently dead. And then, out of darkness, come the woodsmen. It is a group of silent, blackened bearded men. It is forgivable if you confuse these sinister lumberjacks for coal miners. While they perform a strange ritual over the bloodied body, Ray leaves the scene, dazed. And then, we cut away to the band Nine Inch Nails at the Roadhouse.

Could the episode be over? Twin Peaks: The Return was produced by cable channel Showtime, taking Lynch away from the astringent limits of broadcast TV, where a drama has to last one hour, with a firmly set number of commercial breaks. They widely publicized how they gave the author full creative control. Furthermore, Netflix bought rights for territories abroad. And streaming services can be even laxer with running times. Full disclosure: my first exposure to the series took place when I was living in Central America. Netflix would release the episodes a few hours after their American premiere, on Mondays at 2 a.m. With Mondays free, and a natural aversion to spoilers, I would stay awake to catch the episode as soon as possible. Sleep deprivation contributed to the disorienting effect of the structural disruption. I remember being puzzled, thinking anything could happen. And then, it did.

The song ends, we cut to evil Cooper rising from the ground, unscathed. A fade to black takes back in time. Text on the screen registers the date as July 15, 1945. We are in White Sands, New Mexico, just as the USA tests its first atomic bomb. The blast is recreated in stark black and white and blazes away into downright abstract images. A bizarre female figure, floating in space, vomits a stream of gas and a floating orb containing the evil spirit Bob. In a dark, strange fortress, a giant man and a zaftig beauty take notice of the blast and release a golden orb containing the smiling face of Laura Palmer, just as we know her from her prom queen portrait. Primordial good to confront primordial evil. But knowing what becomes of Laura, she is more of a sacrificial lamb.

More things happen in the episode, seemingly unconnected. Some scenes take a more artificial, theatrical style. The woodsmen reappear to haunt a rural radio station. The scene plays out like a pantomime, making its violence even more horrifying. Yet, you can sense this is not random. There is a unifying vision behind it. We try to make sense of it, but by design, it must remain elusive.

Episode 9 takes us back to the structure established pre-episode 8. But the sense that anything can happen, at any moment, remains heightened. The sense of possibility is exhilarating, and it lives on until the 18 episodes run their course. Lynch shuffles his cards at the right time and manages to make the unpredictability of his vision even more volatile. Just send us away with a song, David, before going off into the darkest night.

Watch “Lonely”

“Lonely” is a powerful reminder that no one is ever truly alone, and there is always someone out there who cares and wants to help.

Stream NowWant to get an email when we publish new content?

Subscribe today