"Metropolis": the Original Sci-Fi Dystopia Remains Prescient

Every time you see a silent movie, it is like witnessing a miracle. We might cherish film now, but there was a time, not long ago when they were seen as a disposable piece of entertainment. The instability of nitrate, lack of storage and budget, and downright catastrophes like fires and natural disasters contributed to the erasure of early cinema. According to the experts, only 25% of silent films survive to this day and 50% of talkies. Studios got serious about preserving movies when television came around, and they realized they could license them to TV stations. As cinephilia flourished in the '60s, Film schools were born and helped to develop a deeper appreciation for the art form's past. Saving movies for future generations became a worthy endeavor.

There is intense agony and ecstasy in loving silent cinema. There is agony in yearning for the great films lost to time and carelessness. Think the original 4-hour-long director’s cut of Erich von Stroheim’s “Greed” (1924) or Tod Browning’s “London After Midnight” (1927). And those are just two titles produced by the American film industry. Think of how many movies from other cultures were lost, too, and it’s enough to send you into a pit of despair. Influential institutions like the British Film Institute keep a ledger of its most wanted lost films.

The sadness is tempered by the joy you feel when a major discovery occurs. There is a joke in the archival community about how new elements appear the day after you put out a major restoration. Of course, that is a comic exaggeration, but it was pretty close to the truth regarding "Metropolis," Fritz Lang's socially-minded futurist drama.

The Unmaking of a Classic

In the early ’20, Fritz Lang was the most successful director in the German film industry. The successes of “Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler” (1922) and the double feature of “Die Nibelungen” (1924) gave him enough clout to tackle the most ambitious - and expensive - movie to date. “Metropolis,” co-written by Lang and his then-wife, Thea von Harbou, was a humanistic fable set in a futuristic society where capitalism and exploitation have run rampant.

A magnificent city lives off workers toiling underground while the privileged cavort in magnificent gardens and stadiums. The leader, Johahh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), governs with an iron fist. He can’t predict that his son Freder (Gustav Frolich) will grow a conscience after falling in love with Maria (Brigitte Helm), a proletarian leader who preaches about the arrival of a messiah that will ease the suffering of the unwashed masses - or rather, a “mediator” who will bring together the head (the rich people) and the hand (the workers). In the full “The Prince and the Pauper” fashion, Freder switches places with Georgy (Erwin Biswanger), a worker, to get closer to Maria and taste how the other 99% live. The experience quickly pushes him to the side of the exploited men and women and closer to Maria. When Frederson gets wise to his son’s shenanigans, he recruits scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Kleine-Rogge) to turn a robot into an evil clone of Maria to sow discord among the people and sabotage an impending rebellion.

"Metropolis" was very expensive. It was greenlighted at a 1.5 million mark budget. By the time film production was done, UFA had almost spent 5 million marks. Considering the economic crisis plaguing Weimar-era Germany, it was quite an investment. They negotiated a coproduction with US studios Paramount and MGM to offset risk. It may have been necessary to make the movie without compromising Lang's vision, but it turned out to doom the project in unexpected ways. After over a year of work, Lang premiered a 2-hour, 33-minute movie cut, which turned out to be a box office disaster. It had a theatrical run of 4 months - brief, by the era's standard - and then it closed. It was recut to a 1 hour, 58 minutes version and re-released sometime later. Its fortunes did not change much. States-side, executives deemed the Lang cut unreleasable. They objected to some creative choices that, according to them, could alienate the American public. Thus, a third version was born, timed at 1 hour 56 minutes. World War II sent Lang into exile to America. After the fall of the Third Reich, victorious soviet troops seized many films from the UFA archives, including their sole copy of "Metropolis." A Moscow-based archive received some, but not all, of the film. For many years, Germany did not have a single copy of "Metropolis."

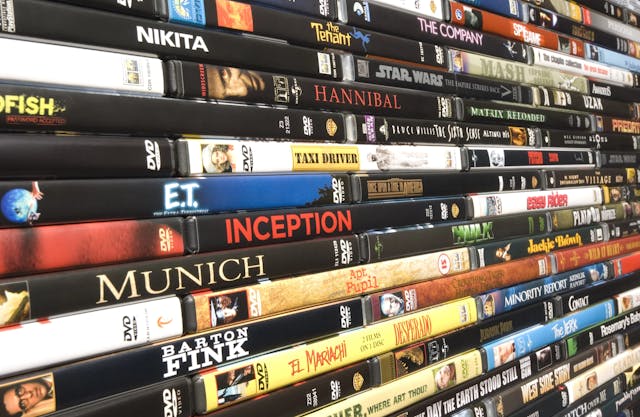

This Machine Eats Men: Freder hallucinates that the machine that keeps "Metropolis" going takes human sacrifices. / Photo courtesy of Entertain Me Publishing LTD.

Building Back "Metropolis"

Over time, there have been several efforts to put “Metropolis” back together again. The most familiar for American audiences was a sui-generis version released in 1986. Italian musical producer Giorgio Moroder secured the rights to edit a version with new music. Fresh after winning an Oscar for the song “Flashdance…What a Feeling!” - performed by Irene Cara in “Flashdance” (Adrian Lyne, 1982) -, Moroder recruited voices like Freddie Mercury, Bonnie Tyler, and Pat Benatar to perform new songs that provided a wall-to-wall bizarre soundtrack for an 83-minute long version. Lost scenes and the controversial choice to convert intertitles into subtitles contributed to the stunted running time. Less forgivable is the tinting of scenes. Yes, some silent films originally used tinting, but that was not the case of “Metropolis.”

Still, you can’t fault Moroder too much. His efforts introduced the film to a new generation and may have been a formative experience for many. The truth is that except for recuperating a pristine, original print of a movie, every restoration is imperfect and limited by the material available. Every new version is a welcomed addition, a testament to our love for cinema.

Occasionally, we get new restorations enriched by newfound materials. There was a 1987 resto, and a 2001. You can add another layer of complications if you contemplate the proper speed to project the film - or transfer it to home video. It’s quite a rabbit hole to fall into, which Glenn Erickson on DVD summarizes masterfully.

A little after the 2001 restoration came out, the kind of news that makes cinephiles weep came out: an Argentinian archive, El Museo del Cine, had a 16 mm, nearly complete copy of the original cut of “Metropolis.” Yes, the one Lang premiered in 1927 at the UFA Palast un Zoo Cinema in Berlin. It so happens that an Argentinian distributor was in the city buying movies and caught it in its first run. He bought a copy to screen it back home. Upon his death, it fell into the hands of an official institution that eventually got rid of nitrate copies of the film due to their volatility. They transferred them to 16 mm. It is an imperfect transfer, but it is Lang’s “Metropolis.” Twenty-five full minutes of footage, previously thought lost, are rescued from oblivion. This is the best Christmas gift for a movie buff.

The Best "Metropolis" around

And so we arrive at the latest restoration of “Metropolis.” Perhaps the most complete I’ll see in my lifetime. It came out in 2010 to major accolades.

The first thing you notice is how beautiful the image is. It’s clear when the Argentinian material appears because the limits of what restorers could do are evident. At least, the scratches and imperfections testify to the indignities to which the beautiful human endeavor of film can be subjected, short of absolute extinction. After a short while, your mind learns to roll with it and appreciate the substantial gains the footage brings to the viewing experience.

Full scenes fleshing out entire subplots resurface, like the misadventures of worker 11811, Georgy, when he takes on Freder’s clothes and sets out to experiment how the 1% lives. We also get his confrontation with Schmale (Fritz Rasp), the scary goon Frederson sends to stalk his son. Equally important is how the background relationship between Frederson and Rotwang gets fleshed out. It’s like something out of a comedy when you discover that Paramount cut the subplot because the name of the woman they both loved was “Hel,” and the word looked too much like, well, “Hell.”

The whole plot feels more solid, fluid, and, for lack of better words, lived-in. It's instructive to see the difference an insert, or a reaction shot previously lost, makes on the movie's rhythm. This is the longest cut ever seen, and yet, the one that moves faster. Time just flies by!

I’d also venture that Brigitte Helm’s performance gains stature, becoming a towering example of an actor tackling a double role. She is the saintly Maria, an advocate for peaceful reprieve between the have-and-have-nots and a romantic ideal for Freder. It’s hard to make goodness interesting, but Helm, as framed and directed by Lang, does just that.

She is equally as good as evil Maria. One can’t spoil an almost 100-year-old movie, so you must know that at a crucial plot point, Frederson and Rotwang kidnap Maria and convert an automaton into a version of Maria they can manipulate to derail an impending workers’ uprising. Fresh out of the lab, evil Maria dresses like the Whore of Babylon, driving men mad with lust at the exclusive Sayawara Nightclub. It’s a shocking development, even more so because the same actress is performing opposing characters with equal conviction. When Evil Maria moves on to derail the poor people underground, promoting a violent revolt, her movements become increasingly twitchy and mechanic. Still, the people are so enraptured by the impending retribution they barely notice.

For such a visually complex masterpiece, the politics of "Metropolis" end up rather convoluted and simplistic. Frederson and the unwashed masses end up in a standoff of self-destructive fury that can only end in mutual destruction. "Metropolis" closes up being a utopia to a fault, aiming for an understanding between oppressors and oppressed. Of course, we don't see what that future looks like after a symbolic handshake, signifying that the hand and the head can reconcile with a little help from the heart. Can't we all get along? Yes, we can! It's easy to imagine the discourse received as simple-minded in Weimar Germany, with Fascism on the rise.

Forever Lost?

Occasional blinks to black remind you there are some frames irretrievably lost. Also, one full scene is conveyed solely by descriptive text on a black screen. This is the best possible outcome, supported by the finding of documents submitted to the censorship office, with a full transcript of all the intertitles in the movie.

Considering the length of the movie and the time that has passed since it first saw the projector's light, it is a miracle that that's the only scene completely missing. Missing scenes are the bane of film preservation and not the sole province of European Silent films. The latest restoration of George Cuckor's "A Star is Born" (1954), a classic Warner Brothers production, used stills, text on screen, and an audio recording to cover a missing scene between Judy Garland and James Mason.

Honorary Citizens of "Metropolis"

This is a minor complaint in light of the achievement that “Metropolis” represents. Its use of scale models, animation, matte painting, and optical tricks is frankly revolutionary. In my eyes, it is better than a thousand CGI frames. Visually arresting, it feeds into early XX-Century art, taking cues from Bauhaus, Art Deco, and Surrealism. Perhaps more importantly, it remains immensely watchable. It’s pure, compelling fun.

If you have not seen "Metropolis," there is no better time than now. It's also the perfect gateway to the wonderful world of silent cinema. Even in incomplete form, it has influenced filmmakers for decades. The entire sci-fi genre as we know it would be very different if it were not for Lang's vision. Case in point: Ridley Scott's futurist dystopia in "Blade Runner" (1982). Queen took snipers of the movie for the official video clip of the single "Radio Ga Ga" (1984). It's a rich irony that the 1927 movie looks better than the official Queen YouTube channel video clip.

None other than Madonna led a virtual, condensed female in her video clip for "Express Yourself" (1988), directed by a young David Fincher, years before his film breakthrough with "Se7en" (1995). Madge was so on board with "Metropolis," she repurposed the most significant line from the film to sustain her feminist battle cry.

Less known in the US is a video clip that promotes one of the last singles of blockbuster Spanish band Mecano. The song “El Siete de Septiembre” (September Seventh, in English) was one of the last singles off their final album, “Aidalai” (1991). The lyrics, about an ex-couple who can’t let go of romantic illusion, have absolutely nothing to do with “Metropolis.” Still, the video is very proficient at duplicating the look of an old silent film, destroyed by time and neglect.

Think of those little morsels as preparation to enjoy the original article. Thanks to luck, serendipity, and the tireless work of archivists and restorers worldwide, "Metropolis" is as close as ever to its original form. This is one of the most beautiful black and white movies ever made.

Watch “Lonely”

“Lonely” is a powerful reminder that no one is ever truly alone, and there is always someone out there who cares and wants to help.

Stream NowWant to get an email when we publish new content?

Subscribe today